This article is based on an actual experience and is intended to remind my fellow CPAs and consultants that we should be wary when reviewing reports of alleged valuations. We should go beyond the simple mathematical calculations and make sure that the valuation preparer is qualified to consult with his, and our, clients. The names, of course, have been changed to protect the unqualified, my client relationships and my career. Admittedly, this is only one example, but it illustrates the perils business owners and buyers face if they don’t obtain a thorough, professionally prepared valuation prior to entering into a transaction.

I share the opinion that there can be legitimate differences of opinion among professionals (even valuation professionals!) and that proper application of valuation methodology can lead to disparate results given different understandings of the underlying facts. This article is admittedly somewhat sarcastic because the preparer apparently did not get an understanding of the underlying facts and has little to no understanding of actual valuation methodology.

Mr. Penny Pincher was responsible for obtaining a valuation on behalf of a company in which he holds a 10 percent ownership interest. Mr. Control owns 70 percent of the company, and the remaining 20 percent is owned by two other individuals. Mr. Penny Pincher is going to use the valuation to establish the amount to be inserted into a buy-sell agreement.

Too often, owners of companies view this valuation clause as simply a documentation issue required by terms of the buy-sell agreement. This valuation becomes a very important piece of information when the buy-sell agreement is triggered; therefore, placing the valuation in the hands of an unqualified or inexperienced person can lead to a terrible result for one party in the buy-sell agreement – and a windfall to the remaining parties.

Mr. Control has used our firm for many services in the past and forwarded the evaluation document for my review to determine whether or not it can be relied upon to establish value pursuant to terms of the buy-sell agreement. I immediately noticed two things:

- The report was called an “Informal Business Valuation.”

- The preparer had five designations, but I didn’t immediately recognize any of them as financial or valuation credentials.

These two initial observations immediately led me to search for the standards under which the “Informal Business Valuation” had been performed. Standards that we typically see include the following:

- The Statement on Standards for Valuation Services (SSVS), as promulgated by the AICPA.

- Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, as promulgated by the Appraisal Standards Board of the Appraisal Foundation.

The SSVS was created, at least in part, to prohibit CPAs from preparing informal valuations upon which our clients might rely at their own peril. The preparer of this Informal Business Valuation was not a CPA. Thankfully.

I found no mention of any standards under which the valuation was prepared. As I continued my review, this was not surprising. The report contained 16 pages, of which only two pages were actually related to the subject business. One page had a schedule of ownership and an allocation of the Informal Business Valuation among the owners. The second page had several formulas for various methods to derive the Informal Business Valuation. Apparently, this single page gave Mr. Penny Pincher the impression that the Informal Business Valuation yielded a reasonable valuation for use in the buy-sell agreement.

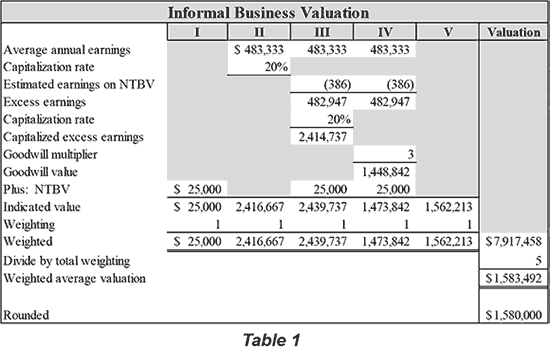

The following table provides a quick summary of the methods used in the “Informal Business Valuation” and serves only to highlight the problems with the report obtained by Mr. Penny Pincher. This article will not address the proper application of these methods, nor is the discussion that follows intended to imply that the various methodologies were correctly or incorrectly applied.

The five methodologies employed by the preparer were as follows:

- Book Value Method, based upon net tangible book value (NTBV).

- Straight Capitalization Method.

- Capitalization of Earnings Method (Preparer Assumes a Going Concern).

- Years’ Purchase Method.

Discounted Future Earnings Method (Preparer Assumes a Three-Year Life Based on Contractual Relationships).

The preparer used these five methods to derive separate indications of values ranging from $25,000 to $2.44 million. He then weighted these five methods evenly to calculate an Informal Business Valuation of $1.58 million (Table 1). On the surface, this Informal Business Valuation falls near the values indicated by the fourth and fifth methods applied and is mathematically correct, leading a potential client to reason that the valuation makes sense.

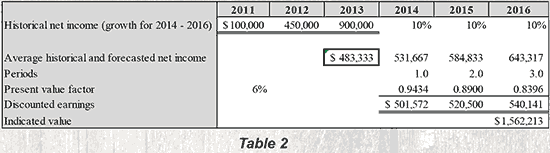

Table 2 shows how the Discounted Future Earnings Method was calculated. Upon receiving the Informal Business Valuation, I dug just a little below the surface and found a few of the problems common to valuations prepared by unqualified individuals:

- Randomly assigning weights to all methods performed whether or not they are relevant.

- Randomly assigning weights to prior years’ earnings for multiple years in spite of the fact that the company is growing significantly.

- Failing to gain an understanding of the valuation subject.

These three failures resulted in my conclusion that the preparer failed to understand valuation theory and related methodologies. My impression is that the preparer indeed had his “black box,” and he used the same methodology and weighting for all of his Informal Business Valuations.

Weighting Randomly Assigned to Methods

First, I questioned why the Book Value Method was assigned a weighting equal to the other four methods. Generally speaking, a going concern will have far more value than that indicated by its reported book value unless that going concern was recently acquired and all assets have been stepped up to fair value. In this case, the Book Value Method yields a valuation of $25,000, which is far below the values indicated by the remaining four methods used by the preparer.

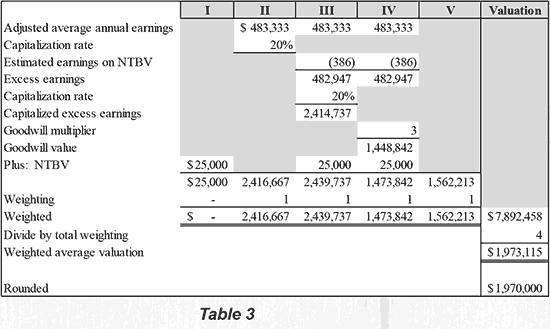

I talked with Mr. Control, who stated that the subject company will remain in business indefinitely and is not asset intensive. Accordingly, I suggested that no weight should be assigned to the Book Value Method. While I was not engaged to perform a valuation, the simple math would result in a revised indication of value amounting to $1.97 million, or 25 percent higher than concluded in the Informal Business Valuation. See Table 3.

Upon eliminating the random weighting assigned to the Book Value Method, the revised indication of value is $1.97 million, falling in between the value of approximately $2.4 million derived under the second and third methods and the $1.5 to 1.6 million derived under the fourth and fifth methods. At least we are in the ballpark!

I dug a little further.

Weighting Randomly Assigned to Historical Earnings Streams

I talked with Mr. Control and pointed out that the preparer used a straight average ($483,333) of the past three years’ earnings performance, which would indicate that there is a high likelihood that earnings will recede from the levels achieved over the past two years. As noted in the table above, earnings grew from $100,000 in 2011 to $900,000 in 2013. Mr. Control stated that there was a low probability that earnings would recede given that the company is adding new customer contracts.

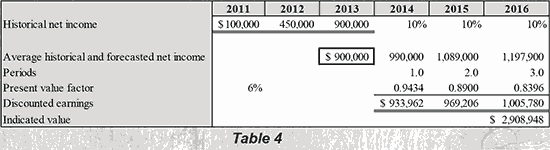

Mr. Control stated that earnings are expected to grow by 10 percent over the next three years, so I again made an adjustment to the preparer’s Informal Business Valuation by using the most recent year’s earnings performance for the basis of mathematically recalculating the indications of value derived under methods two through four. In doing so, I replaced average annual earnings of $483,333 with the most recent year’s earnings, $900,000.

The Discounted Future Earnings Method was recalculated to be $2.9 million, as seen in Table 4.

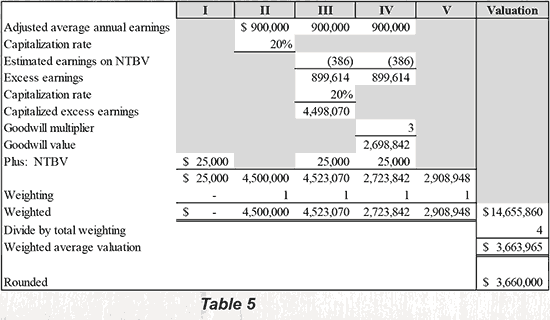

Combining our two changes, eliminating the random weighting assigned to the Book Value Method and eliminating the random weighing assigned to 2011 and 2012 earnings streams that are not reflective of the company today, yielded a revised mathematical calculation of $3.7 million, or 132 percent higher than reflected in the Informal Business Valuation. See Table 5.

Understanding of the Valuation Subject

We now have a valuation range of approximately $2.7 million (methods four and five) to $4.5 million (methods two and three). The key driver behind the difference in these numbers is that the former methods assume that the company will be a going concern while the latter methods assume that the company will continue for only three years and there is no residual value due to the nature of the customer contracts in place and the business itself.

The preparer did not bother to gain an understanding of the company. He had his black box with built-in formulas and defined weightings, and the arithmetic worked. However, the built-in formulas and defined weighting do not apply to every company, and certainly not to this one. Mr. Penny Pincher had his slick-looking 16-page report and he was ready to insert a valuation of $1.58 million into the buy-sell agreement. That amount was a far cry from the amounts ranging from $2.7 million to $4.5 million indicated in the immediately preceding table.

Impact on My Client

In my discussion with Mr. Penny Pincher,he made it clear that he valued a low fee and assumed that the valuation service would be equal to the service that he would receive from a credentialed and seasoned valuation professional. He definitely saved money compared to what he would have spent with a qualified valuation professional; however, he received nothing of value in exchange for his expenditure.

For the sake of discussion, let’s assume that the company is a going concern, will be in existence for more than three years and is appropriately valued using an income approach. The revised value of $4.5 million indicated by methods two and three in the preceding table are reflective of a going concern value, whereas the values indicated by methods four and five are refl ective of customer contracts that will cease in three years for a company that will have no remaining value.

If the true value of the company is $4.5 million and Mr. Penny Pincher is allowed to use the Informal Business Valuation of $1.58 million, then there could be dire consequences for my client, who owns 70 percent of the business. If he agreed to the buy-sell agreement and passed away within the next year, then his estate would be bought out at a price that would be understated by at least $2 million.

This Informal Business Valuation, obtained to fill in the blank of the buy-sell agreement, is haphazard at best and is no real indication of value. As valued consultants to our clients, we should remember to go beyond the math and truly understand the value drivers for the companies and their owners, whom we serve.

Originally printed in the Tennessee CPA Journal.